Jerry Lieblich in conversation with Hannah Bird and Claire Tumey

Newly-minted indie theatre collective MIDDLE SISTER (Claire Tumey and Hannah Bird) sat down with playwright and director Jerry Lieblich to talk about their new play, without mirrors, running at The Brick Theater from February 12-28.

Claire Tumey: Our first question is: how are you today? What's in your literal and metaphorical bag?

Jerry Leiblich: Today I am pretty good. Pretty good. David is working by himself today, and I'll check in with him tomorrow and work with the designer. So I got a day to be very slow. I went to yoga, meditated; I finally got a little bit of time to practice piano, which I had not had time for the last few weeks.

Hannah Bird: Whoop!

JL: And the news was announced two nights ago, that the director from my show last year [Paul Lazar] got an Obie.

CT: We saw that! Very exciting!

HB: Yoga and Piano.

JL: Yoga and Piano. Even for a show like this, where our rehearsal days are not very long and half the time David's working on his own, it's still exhausting. Even when I’m the playwright and I have the least to do, I sit there, I watch rehearsal, and then I'm like dead. So when I have a day off, I try to really use it. So locally very good. Globally, terrible.

CT: Right, right, right. Yeah. We do what we can! Well, we're so excited to talk to you, because [Hannah and I] are also currently delving into the fringey, independent theater producing world. Tell us about your company, Third Ear: what led you to start it, how it;s going, how we’ve made it to without mirrors!

JL: So Third Ear is sort of an outgrowth or an evolved Pokemon of a previous company called Tiny Little Band, which I founded in 2012 with a director friend of mine, Stefanie Abel Horowitz. It sounds fairly similar to you guys. We had been working together, and we were like, ‘let's make a company!’ And that partly came out of wanting to make devised work together, and [Stefanie] wanted to have more of a hand in the writing, and I wanted to have more of a hand in the directing. I was also just interested in what can happen in a devised process that can't happen in a long writing process. So we had that company, we made like 3.5 shows together, and it was great! And yet I think part of the impetus or part of the interest of that company was that the 2 of us had quite diverging centers of aesthetic gravity. For a while that was very interesting, but I think as we both matured as artists, the gulf just became too big. So we stopped doing that, we became friends again (which was very good). She’s in West Virginia shooting a movie that's an adaptation of our 1st show together! But shortly before we dissolved that part of the company, we had gotten 501 C 3 status. And so when we broke up as a company, I kept the legal entity and then sort of sat on that for a bit. Eventually, I came up with the name Third Ear. I don’t quite remember the origin point, but, you know, my plays are very language-y, generally.

HB: Like the Third Eye, but...

JL: Yes, exactly.

CT: Oh yes! That’s very very clever.

JL: So thinking about, like, yeah, like what is it like to have sort of an inner looking experience? But also, I don't know, Third Ear is sort of freakish.

HB and CT: Yeaaaahh!

JL: It felt like it held those 2 meanings in a good way. That it wasn't too woo, but it had at least a whiff of woo. A little frisson of woo. I made a website in, I don't know, late 2019.

HB: GREAT time to make a website.

JL: SUCH a good time to say, ‘Hey, World, Here I am!’ Yeah. And then, The Barbarians, which was the show from last year, was supposed to happen in 2020. Barbarians, of course, got canceled. I left the city for several years. I was like, ‘maybe I'm never moving back.’ And then, kind of as COVID [lockdown] was winding down, I had a production opportunity at The Tank to do a show called Mahinerator, and that was sort of the first, ‘let’s give Third Ear a go!’ And then it's been all very– and this was advice that I got from Paul Lazar about Big Dance Theater– It's all been just step by step. I think I've met people who try to make a theater company where it's like, ‘what's all the architecture we need’ and sort of designing it from the top down? And I think that can work, but it's not how I work. And so instead, it's just been like, ‘okay, time to make the next project: Who and what do I need for that?’ And then afterwards, ‘what's gonna make the next project a little bit easier’ and sort of slowly building the house as I'm living in it?

CT: Like an iterative process, yeah. We kind of operate in a similar way where it's like, very unilateral, horizontal. And then the next time it's like, ‘okay, let's expand’, as opposed to, yeah, what you were saying, trying to take on too much at once.

JL: Or design things too much before you know what they are in space and time, and like what the relationships are, what you actually need.

HB: And that's such a mode that we have to operate in as DIY too. I wonder if you see it as I see it: as a way of protecting your artistic community from burnout.

JL: Yeah, I think about that more and more. I have so many friends who are absolutely brilliant actors, some of the best people I've ever worked with. Every day I'm like, ‘god damn, I gotta put Emma and Dan in another play!’. I try to make myself a steward of these people. That sounds paternalistic or something, but it's like making a home for people.

HB: We build something for each other and for all of us.

JL: Exactly. And I think so much of it is out of necessity to me. I've had moments in my career when larger institutions are interested in what I'm doing. There may be moments like that again. And yet, in all the in-between time, I'm glad that I have a way to keep doing stuff, and not fully rely on that institutional support.

HB: Kind of branching off from that: what is exciting to you about putting this play up at The Brick? It's such an awesome space, a pillar of the independent community.

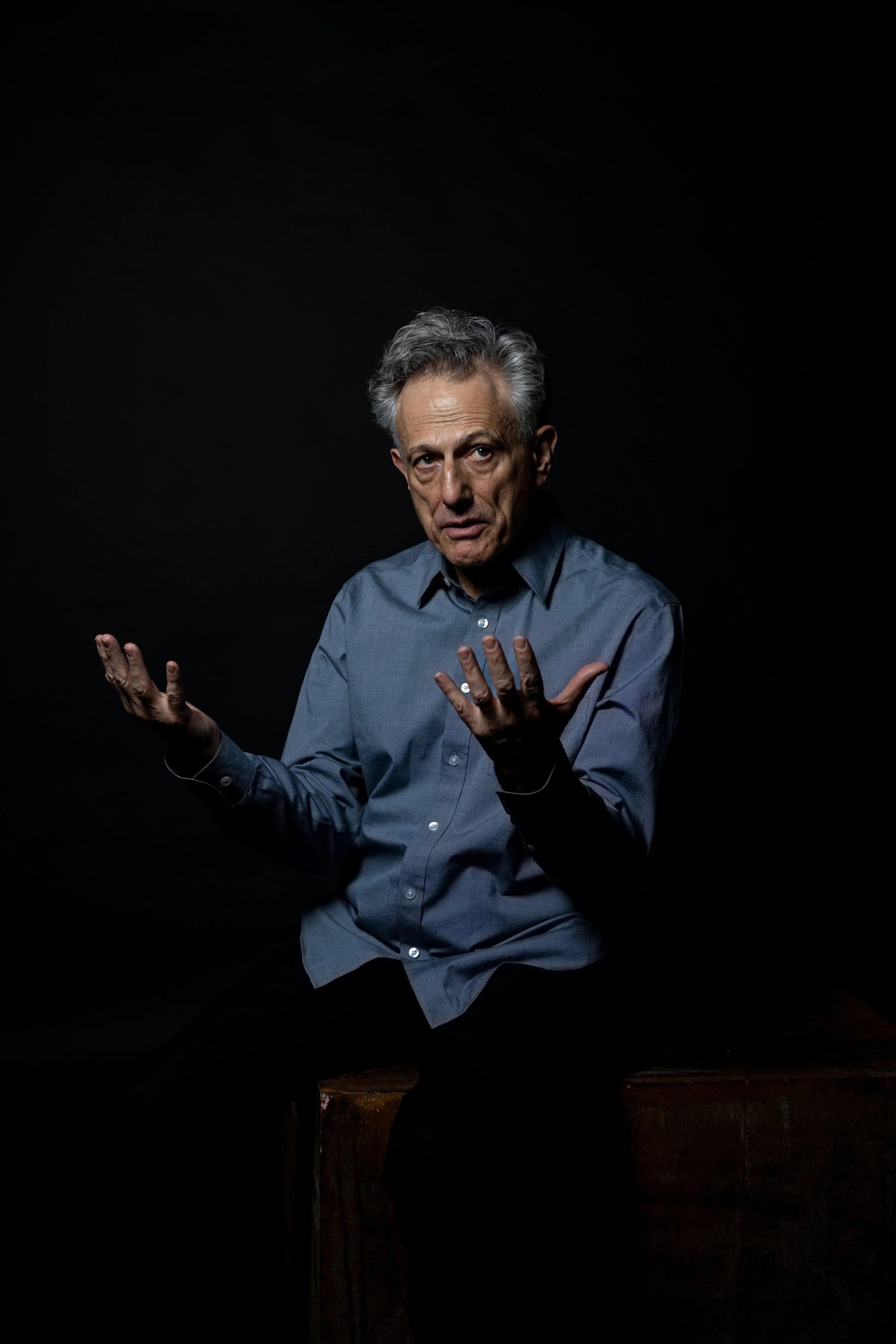

photo: Jose Miranda

JL: It is, yeah. Theresa [Buchheister] was the one who first programmed this play. I was hanging out with them the other night, and it occurred to me that they're the Mayor of The Downtown.There's a certain kind of moral authority they hold; they hold the community together in such an important way. I just love the work they were doing with The Brick. And Peter [Mills Weiss] and I have been buds for a long while. We're basically exact contemporaries, and he was making work when I was starting to do Tiny Little Band stuff, and we were always just sort of side by side in these things. I deeply respect his aesthetic and his ethos, and I think that's coming through in all the programming that he’s doing. All the work [he programs] feels interesting to me, but also there is this ethos of community building, of treating people well, of, like, not making these thick, professional walls. Peter saw an early reading of this, and he was like, ‘yeah, this is a big swing! And that's what I want to use the space for.’ And so it feels great in that way. This is a risky piece in many ways, though; the closer we get to opening, the more I feel like, ‘yeah, this is really good!’ Maybe, ask me 2 weeks ago, I wouldn't have said that. I think it's quite vulnerable as a piece. And strange. And so being in a place where people are down for that is all really good. And The Brick is small, which I love! A house of 44 seats feels full, fast, and that's really nice. And David is giving an extremely delicate performance that everybody can be close to, which is great, you know? I don't know, it wouldn't work in Madison Square Garden.

CT: Although I’m dying to get David Greenspan on a JumboTron. Someone's got to do it eventually.

JL: I mean, there was a draft of the design of this that involved something like that.

HB: Oh my gosh.

CT: Pleeaaaaase. Hello?

JL: Thankfully, that was scrapped, but you know.

HB: I actually worked with David a few years ago on Lunch Bunch. His pronunciation of the word sandwich. Everytime I read the word sandwich, I'm thinking of David Greenspan saying ‘soonnddwuiicche.’

JL: He gives pretty iconic line readings. When I first moved to New York, I interned at Playwright’s Horizons, and the previous season they had done a play of his called Go Back to Where You Are. I didn't even see the play, but I learned his line reading because everybody would just go around the office saying, “Charlotte, Fitzmaurice! Pleasure to make your acquaintance!”

HB: I feel like this play has lots of potential for [iconic David Greenspan line readings].

JL: He's doing a lot of exciting things. It's funny, some of his first drafts of performance were much more externally theatrical. And then he sort of figured out how to internalize that, which is very interesting. He's really quite masterful at continuing to change his vocal register and keeping your ears fresh. He turns these hyper tight corners, where he's in one emotional space, and then suddenly in a different one, and then suddenly in a different one, again and again and again. There’s beautiful music to it.

CT: I saw The Barbarians. I saw it twice! I was really engaged by the attention to detail, and then also, just, the liberties that you take with the English-ish. I was excited to come back because I knew there was more to look at, more to think about. And so I was curious to know how that creative process of creating these surreal verbiage worlds works for you. Do you start with images? Do you start with the words first? Or a secret third thing?

JL: It's a secret third thing. Martians bore a hole in my head, and then the play just comes out.

CT: That’s cool.

JL: There’s a poet– we’ll go on a slight tangent– named Jack Spicer. Amazing poet from the 70s, San Francisco. There’s a lecture series he gave at a university where they asked him about his poetry, and that was the answer he gave. He was like, ‘oh, the Martians just, like, tell me the poems.’ And they were like, ‘okay, yeah, yeah, but seriously.’ And he was like, ‘no, no, it's the Martians.’ And then he gave a beautiful series of lectures on poetics about what it is like to receive poetry. It's astounding. Like, unclear if he's joking. Yeah, I... First of all, thank you. And I'm so glad you came twice. That's incredible. That's my dream. I think part of the goal is to make things where you can't get it all on one go. Yeah, I tend to write from my ears. I really write from sound. So The Barbarians, and without mirrors, and Mahinerator, were all plays that just came from, ‘oh, I think I know the first line.’ And then I'm just, just go, go, go, go, go, and just try to let go of any kind of conceptualization, or knowing where I am, and just think, ‘what's the next interesting word?’ again and again and again and again. It’s like walking with the fog right in front of my nose.

HB: Wow. That’s beautiful. Off the cuff.

JL: So, that will get me something, right? And then the editing process is often, again, getting my nose right next to it. I tend not to try to think about macroscopic structure. I try instead to just think, every tiny moment, how can it be more interesting? So, for Mahinerator–which is a play that's in almost English– he's like, you know:

“When I was what a mere pipsquirt, rightly outta notlike going onto no right institutionated educashamal restructurator on account of the constrictions my parentals in our woe-beguiled den what for the brainly-wiping natures of such facturaries of obedience memorandum…”

HB: Right.

CT: Well, yes!

JL: A lot of it came out kind of that way, and then every time there was phrase that felt too clean, I would break it and either put the wrong word in there, or cut against the sound in a different way, or add an extra syllable where there shouldn't be an extra syllable, so that then every moment starts to become more interesting. In The Barbarians, I wasn't doing exactly that, but it's still, ‘how can this moment be a little more interesting? How can the word be a little more surprising?’ And I've learned to just trust that if I'm really keeping my focus very, very tight, and it's like, ‘this moment is good, and this moment is good, and this moment is good,’ the totality of the thing will be interesting.

HB: You're weaving the web as you go along. There's no master plan.

JL: For sure. Once I'm in rehearsal, that's when I start to see more macroscopic things. I need to start hearing it in order to step back from the canvas, to find what's captivating about it.

HB: I love hearing you bring up poetry because that was one of the things I was curious about when I was reading it. I'm excited to hear about how that rhythm comes to life in production. Have you been feeling that in the room? Do you feel the beat of the play move along with you?

JL: Definitely. David is a sensitive enough performer that he knows how to pay attention to a line break the same way he knows how to pay attention to a comma. Sometimes the line break is about rhythm, but sometimes that rhythm is about creating a multiplicity of meaning. He's able to bring out all those different kinds of meaning, which is great. This play… which is very abstract and very opaque in many ways… my hunch is that many people will experience it almost as a piece of music. David is such an emotionally rich performer, that I think some people will experience it as... like, ‘I'm feeling something going through this, and I don't know why, but the feeling is there, there's a movement.’

CT: When I was reading it, it felt transient, meditative. To me, it’s a play about metamorphosis, about change. And then, of course, I was thinking about [Plato’s] Allegory of the Cave the whole time, so that was a visual in my head. How do you hope [the themes of the play] exist in conversation with your other work, work that's going around in the theater world right now, or even the world at large, you know?

JL: That's a very good question. I mean, there's like 7 different questions there; I'll ping pong around. I've written many plays about change; it seems to be a theme that I come back to again and again and again. And I can psychoanalyze myself and think it's because I'm queer or, in the words of the play, “have a complicated gender.” But I think it's also that I'm just interested in what it is to just get older and change and become. I've written several plays about people turning into other people, quite literally. Where this play is a real departure from a lot of my other work, is that it's not funny. There's moments of humor, because David is very funny. But the emotional register of this play is different from a lot of other things that I've done. Partly that's a reflection of where I was when I wrote it, but also it's a reflection of the time we're in, you know? There's a great need for humor and clownishness right now, and there's also a need for a space of despair, of confusion, of bewilderment. And sitting in that, in a way that's not being... I mean, who the fuck knows where we're going, you know? To sit in that unknowing without a sense of panic–which is different from without a sense of outrage, you know?-- but not panic: to say, ‘things are changing, and they're changing, and they're changing.’ It's a powerful spiritual exercise, at least. So, I hope it resonates with what's going on in the world in that way. [When I was writing it], I was just really feeling through the language and also really feeling through... yeah, the depression I was in at the time. I was at the end of a relationship, I was living in a place that I really didn't like, I felt very lost, at a dead end. Sitting in those feelings was… you have to release it some way. It can be very clarifying for me to turn a question of my life choices into a question of a comma placement. It externalizes [your choices] and lets you kind of deal with [them] in a different way. An image I kept coming to was like squeezing a tube of toothpaste: just express[ing] everything. Rather than communicate, just, like, put out the thing, press it out, knowing that something hopefully interesting comes out of that, and I think something has.

HB: Well, shall we ask our rapid fire questions?

CT: Is there anything else that you want to discuss before we go to the rapid fire round?

JL: I should cite my sources.

CT: Cite your sources!

JL: The play opens with the line, “I had it in mind to rewrite Shakespeare's Richard II without using his plot character language.” The important part is that that idea is almost a direct copy from a poet named Leslie Scalapino, where she talks about doing that for King Lear. Mac Wellman also did something similar. He has a play called Cat's Paw, which is a rewriting of Don Juan, without any men or talk about men.

HB: Bechdel Test-Mode!

JL: And he describes it as a play that was impossible to write, almost. I just wanted to shout out Scalapino and Mac Wellman.

CT: Yeah, that's kind of one of our last questions: what works our conversation with this one? What are you seeing, reading, and/or watching right now that is informing your work?

photo: Jose Miranda

JL: I was reading a lot of late Beckett, a lot of his weird late stuff. I knew David had an interest in late Beckett, too. I was also thinking about Gertrude Stein while writing it, though I think this text is not very Stein-y, but it is from a misremembered distance. Attempting Stein! I was reading a lot of poetry. Yeah, I know that. Leslie Scalapino. I said, uh, Joan Retallack, Rae Armantrout, Lyn Hejinian, Caroline Bergvall. Caroline Bergwald is of a younger generation, but those other names are from a group called the LANGUAGE Poets, an incredible avant-garde poetry group in the 70s who are a font of inspiration [to me]. Their work is totally impenetrable and it’s great.

HB: Well, this is my favorite question; this is my go-to icebreaker question. If without mirrors was a breakfast cereal, which one would it be?

JL: Can one eat the void for breakfast?

HB: I mean, yeah, you can.

JL: Maybe Cheerios: all made of holes, right?

HB: Great answer. And then, a classic: If you could describe the play in one sentence.

JL: Oh, it's so hard. I wish I could. It’s… an experimental language solo piece, performed by the great David Greenspan, about a person trapped in what they think is a cave, though they're not sure, because they've lost any sense of sensual context, and in that... floating void, are questioning the fundamentals of their selfhood.

CT: Perfect. Succinct. Covers all the bases.

JL: I think the one other thing I want to say is something about process, if that's okay.

CT: We love process.

JL: The design and the performance are extremely minimalized. This is one of the reasons I wanted to work with Kate McGee, who's doing the set and the lights. She's really quite brilliant.

HB: Obie-winning for BOWL EP!

JL: Obie-winning for BOWL EP, among other things.

CT: God, I loved that one.

JL: She's quite brilliant at making empty spaces and doing very little. Yet, what's been very interesting over the course of these rehearsal weeks is we walked in with a design, which was pretty minimal, but still had some serious elements in it that were very interesting. I had some staging concepts that were pretty minimal, but there were some things that were more elaborate and interesting. We were working with them and working with them, and then eventually we're like, ‘these don't work and we don't need them.’ And we kept stripping things away and stripping things away, and we were left with the simple, very, very bare bones, and very essential as a result. Which mirrors the journey of the play as well, right, about somebody trying to strip away their sense of self and see what's left. I often think about– there's the medieval spiritual tradition known as via negativa: Negative theology or apophatic theology. It’s essentially a way to learn the divine by removing: negating and negating and negating and removing and removing, bit by little bit, and all that you're left with is what you can't negate; what is unspeakable and what remains is the divine. It can also be a way of making theater. So, what's been very interesting, and challenging, is making these more elaborate versions, and then letting them go.

HB: What someone said to me one time when I threw away something that I had spent a lot of time making, they were stunned; they were like, ‘wow, you really hold tight, let go light.’

JL: It's hard to do, but it's necessary. You have to give the ego a nice little stroke on the head and say ‘thank you very much, see you later.’ But it's also one of the upsides of working with a very small team and gracious collaborators who are down to let go of things, right? It makes me grateful to not be at a large bureaucratic institution where, like, the set has already been built 3 months ago. It's a funny thing making opaque work; there are ways of doing it that are extremely cold, and that keep an audience at arm's length, and are about shielding yourself. There are [also] ways of doing that, which I at least try to practice, that are vulnerable. Vulnerable because you simply don’t know how an audience will react, if they’ll see in it even a shred of what you see. I think the part of me trying to protect that vulnerable part was like, ‘okay, how can I entertain people in other ways? How can I give them other things?’ And then realizing, ‘okay, no, we can trust what's there. And just trust it, trust it, trust it.’ A lot of what David has said in rehearsal, is just [focusing on] how to let the text sing and let that be the thing.

photo: Jose Miranda

HB: The text is the medieval divine.

JL: That's it. Right. I am Julian of Norwich. Yes.

CT: And it's time to purge!

without mirrors runs February 12-28 at The Brick Theatre. Tickets on sale now at https://www.bricktheater.com/