Simon the Taskmaster: A conversation on dance and systems of command between Nora Raine Thompson, Noa Rui-Piin Weiss, and Miranda Brown

By Nora Raine Thompson

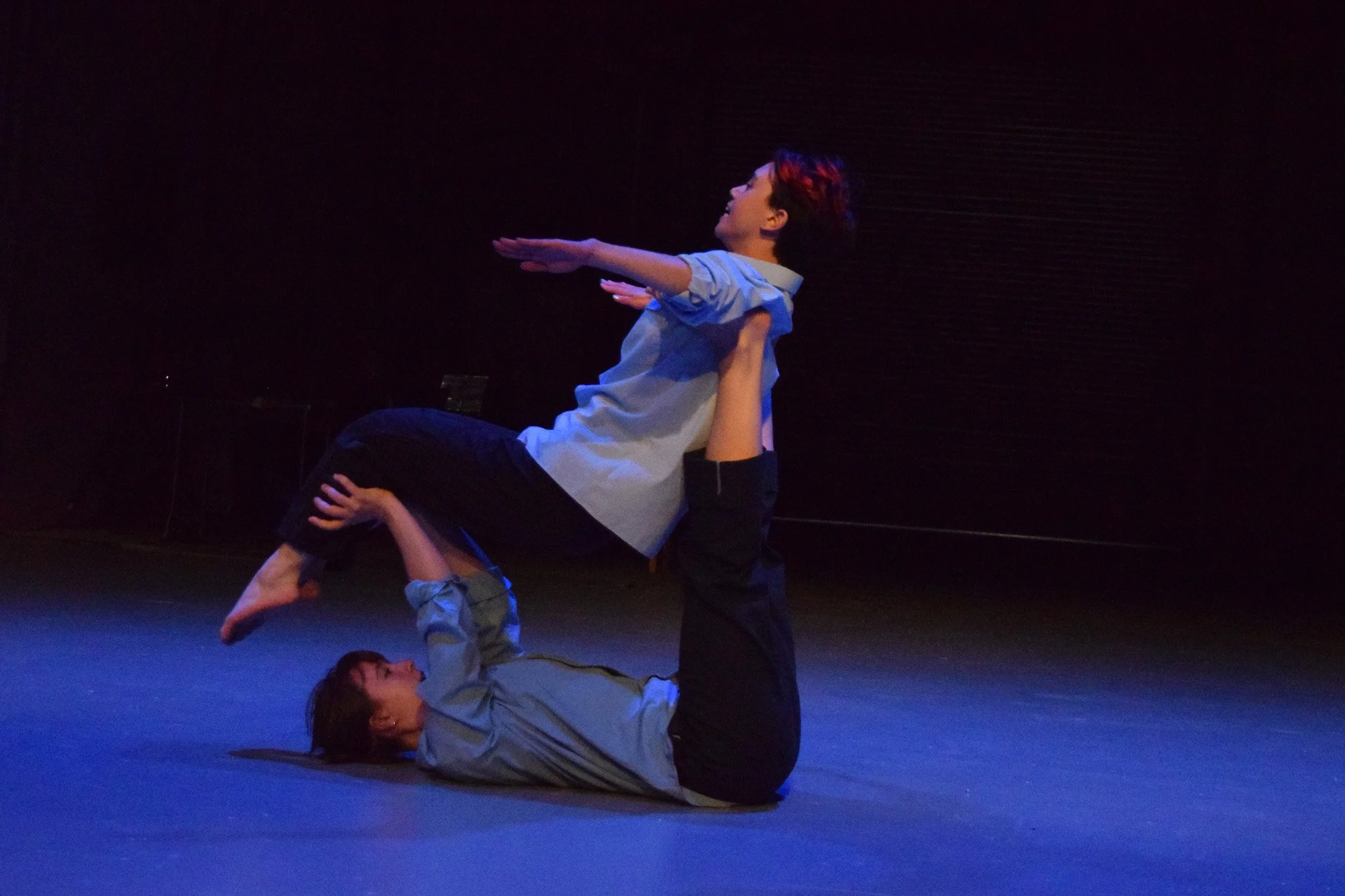

In this conversation, I speak with Noa Rui-Piin Weiss and Miranda Brown ahead of their work-in-progress showing of ¿¡¡simon negs≈≈>:(:{{**, which was presented at the Exponential Festival in January 2025. This was a partner piece to their earlier work, !!simon says~~!:));)$$, which they presented in 2024.

In both works, an unnamed character (presumably, Simon) communicates with them through text instructions displayed on a screen, commanding them to dance in unison, touch the ceiling, dissociate, glisten, torture, even kill. Their attempts to fulfill these tasks (they always try, even as they search for loopholes) is what makes up both iterations of this work.

We are all interested in impossible tasks. My doctoral research uses this idea to study how improvisational dance practices interface with neocolonial and capitalist logics, and how conceptions of possibility get negotiated among choreographers, dancers, and audiences. Noa and Miranda are deploying impossible tasks to craft a choreographed commentary on systems of command, inside and outside of the field of dance. This shared interest led to a conversation about authority, agency, embarrassment, and more.

photo: Eulàlia Comas

Nora:

I would love to start with this figure of authority (Simon) and how it fits into the context of dance, the dance world.

I remember in “Simon Says,” there’s a sequence where the instructions keep changing but you repeat the same action over and over... I think high-fiving each other. I can see you all messing with instructions or commands. It’s like a rehearsal process where an authority figure keeps giving you new instructions, and you’re resisting by repeating the same thing.

Noa:

Yeah, it feels related to when choreographers say they’re working with a task-based structure, but there's a lot of unspoken rules about how it's supposed to look. And there’s a question of who determines success. Who's to say if I’ve accomplished the task if it’s supposed to be impossible? Or they don’t know how it will be accomplished? Who are you to say?

Miranda:

You don’t know!

Nora:

That is a central question in the tasks that I'm looking at in my research, too. Who gets to say if you did it? I think many choreographers have a fraught relationship with that question. They want to say, “it's not up to me.” But then they say things like “try harder.”

Miranda:

Or “that’s it,” or “good job.”

Noa:

Or even, “that was interesting.”

Miranda:

One of the first things Simon says in this piece is “the dancers did a good job.” And despite the fact that we wrote that, it feels good every time. I think, thanks. And it feels especially good when we know that he will then ask for more and more effort, and not be satisfied.

Noa :

Right, and when Simon says, you could put in a little more effort, it actually stings.

Nora:

I appreciate how you two seem to be testing out coaching strategies and seemingly tricking yourself into actually feeling the emotional impacts. Which I think speaks to the tension between just trying to just follow the task, wanting to make an interesting composition, or trying to please the authority figure.

Noa:

Well, there are so many experimental or postmodern dance practices that seem to claim you can trick your mind into making your body do anything, which is not actually true. It can be really cruel to tell a teenager, “it's actually your brain that's not right, and if you can believe hard enough, or if you can believe that you are capable of it, then you'll open up some access to your knees.” But it’s actually just about the depth of your hip sockets! That conflict is really part of our dance trainings, which are both physically rigorous and full of this idea that you have to believe in yourself in a particular way.

Nora:

Right, and in this piece, Simon is saying you have to train, physically.

Miranda:

And he’s saying that the dance needs to be more complex.

Nora:

Which again reminds me of trying to surreptitiously, as a dancer, insert your will or opinion into a process. A friend of mine was recently talking about trying to show her director that their idea was bad by performing it in a particular way, a bad way.

Noa:

And that’s a weird risk, because sometimes you do something to mock, or to show the stupidity of the direction, but then the person in charge says “I like that.” And now your ego is on the line. You’re ultimately the one humiliating yourself in front of the audience.

Miranda:

I will say, half our work is us trying to humiliate ourselves in front of the audience.

Noa:

In a way that is bearable.

Miranda:

In a way that is safe. In the opening improvised section of the piece, for example, we are coping in different ways, through the embarrassment.

Nora:

Why do you want to humiliate yourselves?

Miranda:

(turning to Noa) You had a theory.

Noa:

I think dance is embarrassing.

Nora:

Say more.

Noa:

We don't live in a culture where it's acceptable to move your body in wacky ways in public. The way people get around that is by achieving and trying to prove it’s not silly, show it's actually really cool. Virtuosity, right? Virtuosity is a way of showing that even if the dance is humiliating, I can do it really well. So, as people with complicated relationships to virtuosity and achieving, we are asking, how do you manage not being able to achieve and also not embarrassing yourself?

Miranda:

And so we’ve come to trying to dance in an entertaining way. We value legitimately trying to entertain. We’re trying to make you laugh, intentionally. We don't want you to be bored. We don't want you to just say, what is this weird experimental dance? We want you to find it funny because that's an easier access point into thinking about all of these things. We want to speak to people who don’t dance…

Noa:

Or people who would normally watch a dance and think, that was embarrassing. We’re with them, laughing, and saying, we know it's embarrassing.

Nora:

I wonder if you can genuinely feel embarrassed if it is all planned, choreographed?

Miranda:

Well, I genuinely laugh when Noa says the line about my not having a solid shit in a week. We try to make each other actually feel something, blush. But we also try to stick to what we can get over.

Nora:

What do you do when you can’t or won’t fulfill the task? I know Simon tells you to kill someone in this dance. How do you not do the thing in the frame of this dance where you keep trying to fulfill?

Miranda:

That’s the question, that’s the work in progress.

Nora:

Right, how do you find the loopholes of how to achieve something, or, find your way?

Noa:

Malicious compliance.

Miranda:

We are looking at the internal mental gymnastics you do every day to feel okay, infusing those into the strategies we’re using.

Nora:

Finally, who is Simon?

Noa:

Simon is us, through and through. But we like that there is no audible narrator, that we and the audience have to read the cues in our heads. It’s the voice in your head.

Miranda:

We’re all together, hearing that voice, having that voice. It is an outside political figure, sure, but it is also our own inner critic, telling us we are not succeeding.